When most people think of Valentine’s Day, they picture chocolate boxes, red roses, and greeting cards. But if you’re a beekeeper, February 14th carries a completely different kind of meaning — one that goes back over 1,700 years.

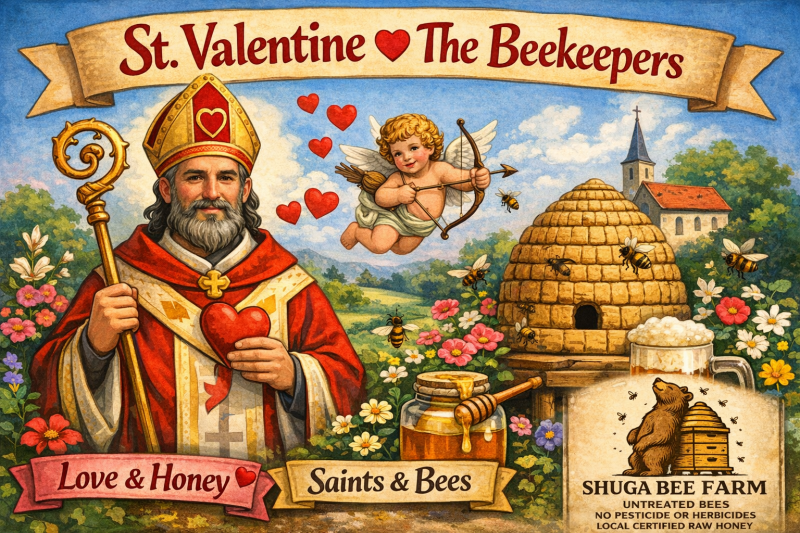

St. Valentine is the patron saint of beekeepers.

That’s not a typo, and it’s not some fringe piece of trivia. It’s recognized history. Alongside lovers, couples, and (somewhat surprisingly) people with epilepsy, St. Valentine has been the designated protector of beekeepers since 496 A.D. — charged with ensuring the sweetness of honey and the protection of those who keep bees.

As beekeepers ourselves for over 14 years here in Johnston County, North Carolina, we think this is a story worth telling. So this Valentine’s Day, let’s go beyond the candy hearts and look at what this ancient connection between love, bees, and the patron saint really means — and why it still matters to us today.

Who Was St. Valentine?

The historical record is a bit murky — and that’s being generous. There may have been as many as three different men named Valentine (or Valentinus, from the Latin word meaning “worthy” or “strong”) who were martyred in the early centuries of Christianity. The most commonly cited was a 3rd-century Roman priest and physician who lived during the reign of Emperor Claudius II.

According to the legends, Claudius had banned marriages because he believed unmarried men made better soldiers. Valentine defied the emperor by secretly marrying Christian couples. When he was discovered, he was imprisoned, tortured, and ultimately executed on February 14th, around 269 A.D. Before his death, the story goes that he healed the blindness of his jailer’s daughter and signed a farewell letter to her — “from your Valentine.” That phrase has echoed across seventeen centuries.

His feast day — February 14th — didn’t become associated with romantic love until the Middle Ages, partly influenced by the medieval English belief that mid-February was when birds began to pair off and mate for the season. That timing wasn’t a coincidence. February is also when nature begins to stir, and for beekeepers, it’s the threshold of a new season.

Why Bees? The Ancient Connection Between Love and the Hive

To understand why Valentine became the patron of beekeepers, you have to understand how deeply bees have been woven into the symbolism of love, fertility, and devotion across cultures — long before Valentine’s Day existed.

In ancient Greece, bees were sacred creatures connected to the divine. The goddess Aphrodite — goddess of love and beauty — counted the honeycomb among her symbols. Her priestesses at the temple of Eryx were called “Melissae,” the Greek word for bees. The Pythagoreans worshipped bees as Aphrodite’s sacred creatures, fascinated by the perfect hexagons of their honeycomb, which seemed to reflect an underlying order in the universe.

Then there’s the story of Cupid (known as Eros to the Greeks), the god of love himself. In one of the oldest surviving versions of the myth, young Eros sneaks into a beehive to steal honey and is stung by the bees. He runs to his mother Aphrodite, crying that something so small could cause so much pain. Aphrodite smiles and reminds him that he, too, is small — yet the wounds his arrows cause are far greater. Love and the bee sting: sweetness and pain intertwined. That metaphor has resonated for thousands of years.

Even the Hindu god of love, Kamadeva, carries a bowstring made of honeybees — representing what the ancient Sanskrit texts called “sweet torment.” The ancient Egyptians believed bees were born from the tears of Ra, the sun god, and used honey in everything from medicine to burial rites. Celtic cultures saw bees as winged messengers between the physical world and the spiritual realm, carriers of wisdom and hidden knowledge.

Bees, in nearly every civilization that encountered them, became symbols of love, devotion, sacrifice, community, and the divine. When the early Church was looking for a patron saint to watch over beekeepers and their sacred craft, Valentine — the saint of love and devotion — was a natural fit.

February 14th: A Beekeeper’s Holiday

Here’s what makes this connection even more meaningful for those of us who actually keep bees: the timing of Valentine’s Day lines up perfectly with the beekeeping calendar.

Mid-February is when the beekeeping year begins to shift. The days are noticeably longer. In parts of the southeastern U.S. — including right here in Johnston County — you’ll start seeing the first early blooms. The queen is beginning to ramp up her egg-laying inside the hive, preparing the colony for the explosion of spring growth ahead.

For beekeepers, February is a month of watchful hope. We’re checking on hive stores to make sure the bees have enough food to make it through the last stretch of winter. We’re lifting the backs of hives to estimate weight, peeking at entrances for signs of activity on warm days, and looking for wax crumbs or early pollen loads that tell us the colony is alive and building. It’s the beekeeping equivalent of holding your breath — and then breathing again when you see those first foragers coming home with tiny baskets of golden pollen on their legs.

Historically, this was also the time when beekeepers would “bless” their hives for the coming season. In the British Isles, bees and livestock were commonly “wassailed” in January and February — a ceremonial toast to ensure health, vigor, and a good harvest. The tradition of telling the bees about important family events (births, deaths, marriages) was taken very seriously across Europe for centuries. You told your bees everything, because they were considered members of the family.

So when early beekeepers looked to February 14th and saw it was the feast of a saint already associated with love, devotion, and protection — it made perfect sense to claim him as their own. Valentine wasn’t just the saint of romantic love. He was the protector of the creatures that embodied it.

He’s Not the Only One: Other Patron Saints of Bees

While Valentine may be the most recognized, he’s part of a long tradition of saints connected to bees and beekeeping across Europe and beyond. A few worth knowing:

St. Ambrose of Milan (4th century) is considered the other leading patron of beekeepers. Legend says that when Ambrose was an infant, a swarm of bees landed on his face and left a drop of honey on his lips — foreshadowing the eloquent words he’d become famous for. He’s often depicted in art with a beehive, and the word “mellifluous” (honey-tongued) is traced directly back to descriptions of his preaching.

St. Gobnait (also known as St. Abigail or St. Deborah) is the patroness of bees and beekeeping in Ireland. Unlike some saints whose connection to bees is symbolic, Gobnait was an actual beekeeper. Celtic lore held bees in extraordinarily high esteem — the Celtic peoples believed the soul left the body as a bee or butterfly. Gobnait’s feast day? February 11th — just three days before Valentine’s Day.

St. Modomnoc, an Irish monk who studied at St. David’s monastery in Wales, became beloved by the monastery’s bees. When he tried to sail home to Ireland, the bees followed his ship — twice — until the abbot gifted them to him. He’s credited with bringing beekeeping to Ireland, and his feast day falls on February 13th. That’s three bee-related feast days in four days — right in the heart of mid-February.

St. Bernard of Clairvaux earned the title “Doctor Mellifluus” (the Honey-Sweet Doctor) for the sweetness and power of his writing, connecting honey metaphor to spiritual eloquence in the French tradition.

It’s remarkable that so many saints connected to beekeeping share feast days clustered around mid-February — the very moment when bees begin stirring back to life across the Northern Hemisphere.

What This Means to Us at Shuga Bee Farm

We’re not here to preach. We’re beekeepers. But we’d be lying if we said this history doesn’t resonate with us every time February rolls around.

Beekeeping, at its core, is an act of love and devotion. You don’t keep bees because it’s easy or profitable. You keep them because you’re drawn to something bigger than yourself — the hum of a healthy hive, the miracle of watching a single colony turn wildflowers into liquid gold, the responsibility of caring for 60,000 tiny lives that never asked for your help but thrive because of it.

We’ve been doing this for over 14 years across three apiaries here in Johnston County. We’ve never used chemicals on our hives. We harvest our honey raw, unfiltered, and unheated. We do it the slow way, the hard way, the right way — because that’s what the bees deserve.

So this Valentine’s Day, whether you’re celebrating with a partner, spending time with family, or just enjoying a quiet day — take a moment to think about the bees. They’re out there right now, in hives across Johnston County and all over the world, doing the same thing they’ve done for millions of years: working together, building something beautiful, and making the world a little sweeter.

And if you want to do something really special for a nature lover or honey enthusiast in your life, we’re still accepting signups for our Host a Hive program — give someone their very own beehive for the season. Now that’s a Valentine’s gift St. Valentine himself would approve of.

Happy Valentine’s Day from our hives to your home.

— Shuga Bee Farm

Want to learn more about our bees and honey? Browse our raw, chemical-free honey from three Johnston County apiaries, or check out our Host a Hive program before spots fill up for 2026.